What is it like to be displaced? Where does one go when deprived of a home, personal possessions, and isolated from loved ones? Refugee settlements around the world offer a place of transitional solace, providing basic nourishment, a pause from persecution, and hope in the form of a path to a new life.

Today there are more refugees and people driven from their homes by conflict, intolerance, and environmental and economic circumstances, than at any point since World War II, according to the UN’s UNHCR Refugee Committee. More than half of these individuals are children.

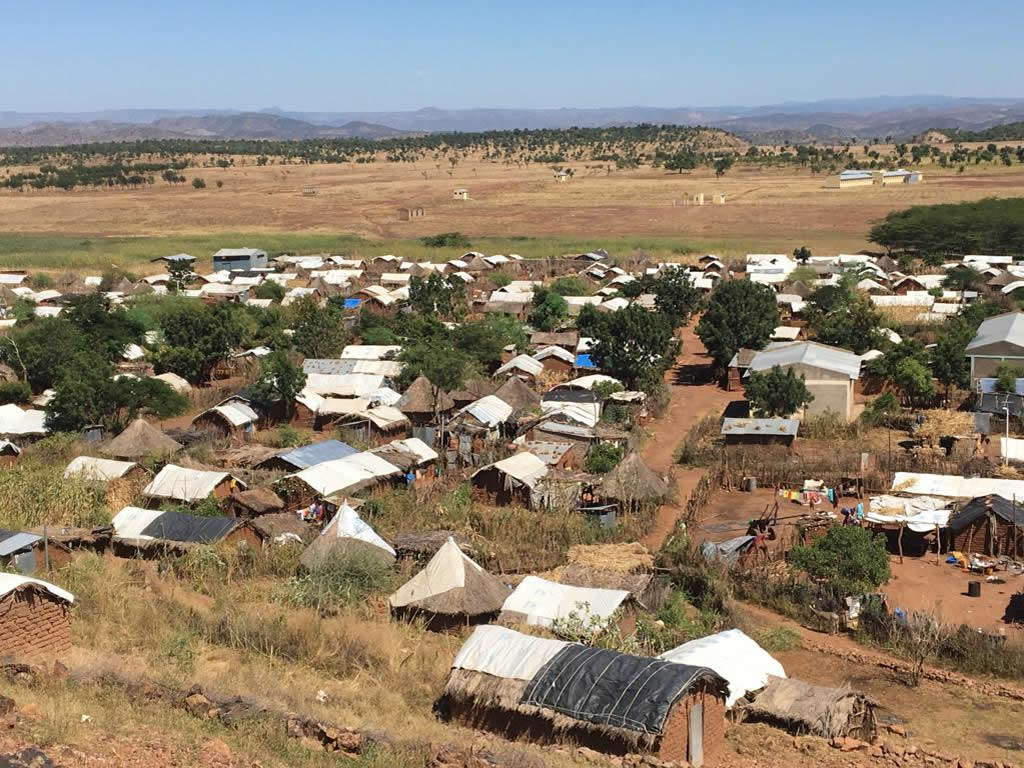

At the Shimelba refugee camp, located in the Shire region of Ethiopia, a majority of the nearly 6,000 residents have fled from Eritrea, a country whose leaders have been accused by multiple UN reports of crimes against humanity. Military service there is obligatory and indefinite in length and religious persecution is rampant. Not surprisingly, the country, which once formed part of Ethiopia’s northern region, has been designated one of the world’s fastest-emptying nations.

“Refugees in Shimelba camp speak of government atrocities back home, ranging from accusations of genocide against the Kunama, including mass poisonings, to government officials shopping at markets and then shooting stall owners due to disagreements over prices,” wrote James Jeffrey for Public Radio International.

“Most say they faced military conscription, religious persecution, arbitrary detention, torture,” said Teshome Kasa, coordinator of the refugee screening center in the Tigray town of Endabaguna, told the Irish Times.

Engineer Andrea Eras is pleased to be using her expertise to improve access to energy in refugee camps around the world. Eras works with the Instituto de Energía Solar of the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (IES-UPM) as a member of its Renewable Distributed Generation and Intelligent Control research group (GEDIRCI). Her team focuses on PV systems, rural electrification, new markets for PV, and business models for renewable energy. The group is also an active member of the UPM Platform on Refugees, which supports projects to improve the quality of life of refugees and their host communities by engaging researchers from a variety of different sectors such as energy, water, shelter, agriculture, and education.

“Most refugee camps do not have access to electricity by the electrical grid, leaving them powered by isolated diesel generators,” Eras explains. “In Shimelba only 5% of the refugee population has access to electricity, on average 6 hours a day. That power is produced by diesel generators with operational time limited by fuel availability, maintenance issues, and lack of capacities.”

“The design and deployment of an optimum generation power system is a crucial aspect to solve one of the main needs of these vulnerable people,” Eras says of establishing distributed energy systems to power the refugee camp. “According to our analyses, microgrids are not only the most cost-effective and reliable system but also these are the most optimum way to involve local people in a business managed by their own.”

By making access to electricity more affordable, power more abundant and reliable, and supporting local cooperative businesses, while also benefiting educational and human health services, microgrids offer a multi-faceted solution.

Microgrids are expected to be deployed in Shimelba to power a Telecenter and to build local energy networks that support construction, agriculture, and communication technologies, while also increasing the level of access to electricity at the household level.

Providing electricity service in refugee camps is a huge challenge. In refugee camps such as Shimelba, incomes far below the poverty line (1.25 USD/day) and few work opportunities mean that energy price structures must be thoughtfully planned. For many refugees, access to electricity can easily represent 15% of a family’s income per month. This presents challenges regarding the economic feasibility of the power systems that Eras and her team designs.

“We use HOMER software in the planning phase to evaluate different configurations of microgrids and to support the decision-making based on LCOE and initial investment,” Eras explains. “Additionally, we use this software to evaluate the operation of mini-grids previously installed.”

Many of the microgrids Eras’ team designs are powered by diesel generators and hybridized with PV and energy storage systems. “With the information HOMER provides, we can improve and strengthen technical quality assessments at the same time,” she explains. “This kind of analysis helps to identify the weakness of a power system at the technological level.”

“HOMER is the most developed software to assess and design hybrid power systems. HOMER allows us to introduce very detailed information related to projects such as maintenance periods of diesel generators. The sensitivity analysis is a real advantage to evaluate many variables at the same time, which is crucial in the decision-making process. Comparing HOMER with other software, this is a user-friendly tool and above all, this is the most suitable option to assess projects realistically.”

Eras emphasizes the importance of a collaborative, human-centric approach to energy provision and system planning. “Power systems cannot be designed only based on technical and economic assessments. Identifying the main needs of people is the most important phase in order to design a power system to cover these needs. The participation of multiple actors and the involvement of local communities is essential.”

In the year ahead, Eras and her team plan to evaluate other energy access projects in refugee settlements around the world, while seeking funding for their current UPM Platform projects. She and her team hope that the microgrids they design will bring comfort and solace to displaced individuals…and ultimately hope.