A June 5 news report shines a light on key concerns at the center of state legal and regulatory debates that revolve around utility-owned and public service-oriented microgrid projects and programs. At issue is whether or not regulated utilities should be permitted to own and operate microgrids.

A June 5 news report shines a light on key concerns at the center of state legal and regulatory debates that revolve around utility-owned and public service-oriented microgrid projects and programs. At issue is whether or not regulated utilities should be permitted to own and operate microgrids.

Advisers have recommended the Maryland Public Service Commission (PSC) deny Baltimore Gas & Electric’s (BGE) request to recover $16.6 million from ratepayers as part of a proposed project plan. The plan would entail deploying two public service-oriented microgrids of 2-3 MW each, Microgrid Knowledge‘s Elisa Wood reports.

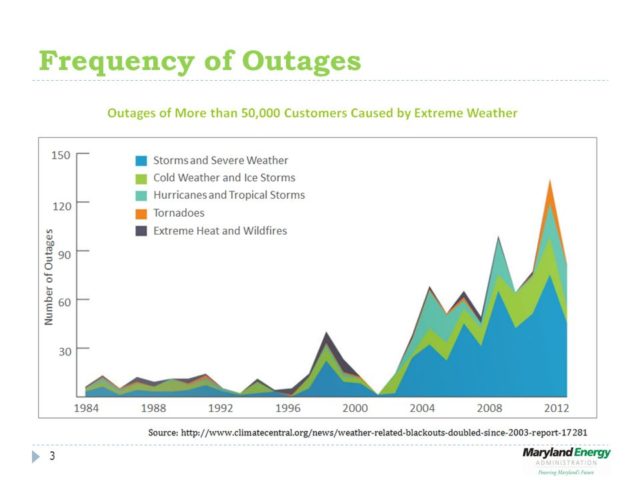

Instead, they recommend the PSC launch a broad-based inquiry of state policies and the various alternatives policy-makers should consider when it comes to opening up the state’s power market to greater microgrid investment and deployment. This course of action would help realize state government goals related to enhancing grid reliability and resiliency as well as reducing greenhouse gas emissions and electricity costs to consumers.

Pilot Community Microgrid Project’s Impact on Ratepayers

The special charges BGE has requested be added to ratepayers’ utility bills were intended to recover the projected $16.6 million cost of the utility’s pilot microgrid project investment. These charges were one of the main reasons the advisers recommend the PUC deny the utility’s proposed plan.

BGE submitted its $16.6 million community microgrid proposal to follow through on an Executive Order and resulting June 2014 report from a Maryland Energy Administration (MEA) Task Force. The order recommended ¨the State focus on the deployment of utility-owned public purpose microgrids through advocacy and incentives.¨

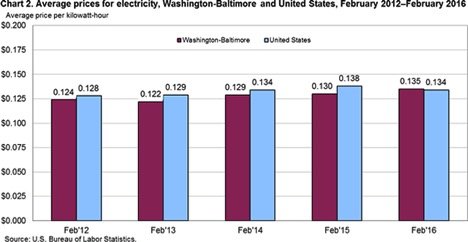

BGE estimates that deploying pilot community microgrids in King’s Contrivance, Howard County, and Edmondson Village in Baltimore City would add about $0.04 per month and $0.48 per year to customers’ utility bills in the first year. This number is based on a residential customer using 930 kWh of electricity per month, MEA summarizes in its response to the utility’s project proposal. Those charges would increase to an estimated $0.13 per month and $1.56 per year given no additional microgrids are deployed.

Furthermore, MEA pointed out that commercial beneficiaries in the two site areas apparently aren’t contributing anything to two proposed community microgrid projects. Moreover, BGE hasn’t conducted any energy-efficiency audits in the site areas.

¨There is no certainty the buildings located within the PPMG [Public Purpose Microgrid] have implemented energy efficiency or renewable energy measures that would enhance the effectiveness of the overall PPMG,¨ the MEA Task Force states.

In conclusion, MEA ¨is still supportive of the concept of public purpose microgrids and recognizes the potential benefits of their future deployment. However, MEA cannot support the BGE proposal at this time because of its impact on ratepayers.¨

Other Points of Contention

Another point of contention has to do with the nature and classification of microgrids, and how related state policy-making might affect the power market, industry, state economy, and life in communities. These issues lie at the crux of debates between utilities and independent microgrid project development and industry participants, as well as among regulators and lawmakers in a growing number of states.

In its report to the Maryland PSC, the advisers state they were not persuaded that “a utility-owned microgrid is legal, let alone that it is of sufficient public benefit to call for ratepayer financing,¨ according to Microgrid Knowledge’s news report.

Regulations in states such as Maryland prohibit utilities from owning generation assets. As microgrids incorporate generation assets, as well as battery energy storage capacity – technically and legally gray area in terms of their classification as generation or distribution assets – in-state regulated utilities are barred from owning them.

This regulation effectively shuts regulated utilities out of competing in a young, fast-growing power market segment at a time when they’re facing technological and competitive business challenges of a breadth and magnitude never experienced before.

Regulated Utilities and Microgrids

These existing regulations haven’t stopped regulated utilities, or rather their unregulated parent corporations, from attempting to capitalize on microgrid growth prospects. The parent corporations of regulated utilities such as Duke Energy have entered microgrid markets both inside and outside the territory of their regulated utilities via unregulated energy services subsidiaries.

In the project proposal BGE parent corporation Exelon submitted to the Maryland PSC this past December, management wrote that it believes recovering the cost of deploying the two proposed microgrids is justified. Their reasoning: microgrids would be able to provide backup and emergency power to support critical public services and facilities for neighborhood residents, businesses, and disaster recovery facilities, such as hospitals and shelters. Similar “community microgrid” projects proposed by regulated power utilities that Exelon owns in Illinois and Pennsylvania are under way, Microgrid Knowledge‘s Wood points out.

Coming Out For and Against

In an interesting twist, another corporation that owns regulated utilities – though not in Maryland – has submitted comments to the PSC arguing against granting BGE permission to proceed. NRG Energy writes that permitting BGE, or regulated utilities in any state more generally, to own microgrids would limit competition and development of the microgrid market and industry.

In addition, end users in Maryland legally have the option of shopping among competing retail electricity providers while utilities such as BGE deliver the electricity and take care of customer billing and accounts. Allowing BGE to own microgrids would likely take customers out of the retail market, NRG states.

Most consumers that would be interested in microgrids, such as hospitals and schools, also tend to actively shop around for electricity providers, the company adds. Allowing BGE to deploy and own community microgrids would remove these customers from the retail market, management argues.

It turns out that nearly half those eligible have not even heard of the retail consumer choice program, the North American Energy Advisory points out in an April 2016 blog post.

Those that don’t choose a retail market supplier automatically receive the standard BGE utility offer. This lack of information is a primary reason the Department of Energy estimates that the average Maryland resident spends almost $3,000 per year on electricity, Matt Heland writes.

The main thrust of Heland’s North American Energy Advisory blog post is Chicago-based Exelon’s regulated-utility acquisition spree, however. Exelon has acquired BGE, Illinois Commonwealth Edison, the Philadelphia Electric Co., and Pepco, which supplies electricity to D.C. The acquisitions, with the exception of Pepco, have been approved with little or no opposition. More important, they fly in the face of state energy policy planks, such as that which exists in Maryland, for preventing any corporation from gaining monopoly power in state energy markets.

That said, Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake and state legislators representing the two neighborhoods home to BGE’s two proposed community microgrid sites support the utility’s PSC project proposal.

In contrast, the Microgrid Resources Coalition (MRC) is neutral regarding BGE’s community microgrid project proposal. Echoing the PSC advisers’ recommendation, MRC suggests the PSC instead launch a study that addresses microgrids and state policy-making.

The potential benefits of microgrid deployment extend beyond providing backup emergency power, the non-profit industry advocacy group points out. Microgrids can improve overall grid reliability and resiliency by providing ancillary services, such as frequency and voltage regulation, provide heat as well as electricity to end-users, and help meet greenhouse gas emissions reduction and environmental goals, according to MRC.

“While resiliency is a primary benefit provided by microgrids, the MRC believes that an exclusive focus on this benefit actually limits the ability of microgrids to meet resiliency goals and fails to recognize that a microgrid undertaken solely for resiliency purposes is unlikely to be self-funding in any meaningful way,” MRC wrote. “The economic, resiliency and environmental benefits of microgrids are mutually reinforcing.”