This blog post was originally published by the Smart Electric Power Alliance (SEPA) on February 19, 2019. It is by Jared Leader & Robert Tucker.

The D.C. Public Service Commission (DCPSC) has assembled stakeholder working groups around microgrids and distributed energy resources (DERs) to drive regulatory innovation. This diverse collaboration of District stakeholders is developing a set of recommendations for the DCPSC on new planning processes and microgrid regulatory framework.

Changing Energy Landscape

As the utility operating environment changes, utilities are faced with new challenges, including aging infrastructure, security threats, natural disasters, environmental policies, declining utility sales and revenues, and increasing penetration of DERs. To address these pressing issues, utilities, developers and regulators can embrace an emerging opportunity — microgrids.

Not only can microgrids be used as a tool for increasing a customer or community’s energy resilience, but they can also be used to increase grid capacity and reliability. Microgrid development can be viewed as a function of a changing utility landscape, as the price of technology decreases and the customer’s eco-consciousness increases. However, leveraging the full value of microgrids requires untested business models that may not be accounted for yet in the current regulatory frameworks.

Change Calls for Regulatory Innovation– and Innovation Starts with Stakeholder Engagement

The energy landscape is rapidly changing, requiring utility and non-utility stakeholders to come to the table and get to work. As the grid modernizes across the nation, an opportunity arises for interdisciplinary collaboration among key stakeholders, including utilities, developers and advocates.

The Smart Electric Power Alliance (SEPA) Advisory Services team is under contract with the DCPSC to help accelerate the grid modernization transition and facilitate stakeholder engagement in D.C. SEPA is convening all District stakeholders with the goal of tackling the myriad regulatory, policy and operational challenges associated with microgrids. SEPA is also addressing other key grid modernization topics like Non-Wires Alternatives (NWA), Rate Design, and System and Customer Data.

As you can imagine, it takes a village of engaged stakeholders to tackle these issues and develop thoughtful solutions.

In D.C., there are three notable topics that stakeholders are highly engaged with: 1) utility ownership of energy storage, 2) distribution planning and NWA considerations, and 3) microgrid regulatory framework.

Energy Storage Ownership

After the electricity deregulation in the late 1990’s, utilities divided into either generation or transmission-and-distribution-only (T&D) companies. T&D utility companies weren’t allowed to own generation assets. Over the past 10 years, DERs including energy storage have grown tremendously and regulators in D.C. and across the country are now grappling with rules around utility control, ownership and operation of energy storage. This regulation varies from state to state, with some only just getting started.

- California: In 2013, California set the first — and most aggressive — energy storage procurement target in the U.S. As a result of AB 2514, the target is 1,325 MW (limited utility ownership of 50%) of operational storage by 2024 by the three investor owned utilities (IOUs). In 2016, a second bill, AB 2868, was signed into law allowing 500MW to be rate-based by the three IOUs. AB 2868 allows utility ownership of behind-the-meter storage, as long as it does not unreasonably limit or impair the ability of non-utility enterprises to market or deploy energy storage systems.

On February 26th, an Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) in the state proposed an order requiring utilities to issue requests for offers (RFOs) for energy storage facilities without any bias towards ownership model. It is currently being reviewed the the IOUs and will be considered by the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) at its March 28 meeting.

- New York: The New York Public Service Commission (NYPSC) adopted a regulatory policy framework making utility ownership of DERs the exception rather than the rule. The exceptions permitting utility ownership of DERs are: 1) to meet a system need, 2) DERs that are integrated into distribution system architecture, 3) involve low- or moderate-income customers, or 4) demonstrate learning from pilots.

- Maine: In February 2018, the Maine Public Utility Commission ruled to allow utility ownership of generation and energy storage — only if the asset improves grid reliability and efficiency.

- Illinois: In February 2018, the Illinois Commerce Commission (ICC) issued a final order which approved the Bronzeville microgrid and directed third party ownership of generation, coupled with ComEd ownership of the energy storage. The ICC also determined that due to the microgrid’s distribution function, ComEd can recover costs via distribution formula rates.

- Massachusetts: In 2016, HB 4568 defined storage as a “commercially available technology that is capable of absorbing energy, storing it for a period of time, and thereafter dispatching the energy,” and may be owned by a utility. Just last week, the Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities (DPU) issued two orders on the state’s storage rules that open up revenue streams to the utility, third party developers and customers. The prospect of energy storage ownership is still up for interpretation.

- Texas: The Public Utilities Commission of Texas has an active docket No. 48023 considering energy storage ownership, and released a report to legislature asking for guidance on ownership.

Distribution Planning

Utilities have traditionally been responsible for planning, operating, and maintaining their systems. With the increase in third-party providers and customer-facing solutions, several jurisdictions have looked to stakeholders for input on enhancing distribution planning to provide market solutions, such as NWAs.

Despite being considered niche products in the past, microgrids are proving to benefit not only the internal customer, but also the grid as a reliability or capacity resource. However, in order successfully implement the microgrids, regulators and utilities must encourage a stakeholder-informed and transparent planning process.

In D.C., Pepco Holdings (PHI) has embraced the concept of considering NWAs and proposed its own integrated distribution planning process as part of the D.C. working group. Last year, the Commissions in New York and California ordered IOUs to adopt integrated distribution planning (see New York’s 2018 IOU DSIPs and California’s integrated resource planning framework.)

Microgrid Regulatory Framework

The microgrid regulatory framework is designed to lay the foundation for future microgrid development in the District. This is noteworthy because key stakeholders believe that regulatory certainty would help facilitate future microgrid development.

For example, one stakeholder stated in the MEDSIS Staff Report from 2017 that by“establishing simple categories of microgrids, straightforward packages of regulation can be developed.” These packages of regulations or regulatory framework will outline how the Commission should or shouldn’t regulate microgrids.

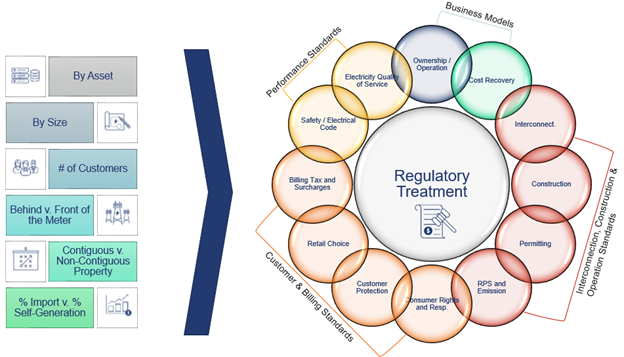

After five meetings, the microgrid working group has identified six potential practical business models and is currently evaluating the regulatory implications of each. It’s important to keep in mind that microgrid technologies and applications are constantly in flux, and that these “packages of regulation” must be flexible and adaptable. Minor variations – for instance, number of customers, behind-the-meter vs front-of-the-meter, contiguous vs non-contiguous, property and size of the assets – can impact its regulatory treatment.

The four components of these “packages of regulation” are: 1) business models, 2) interconnection, construction & operation standard, 3) customer (rights and/or engagement) and billing standards, and 4) performance standards. In May of this year, SEPA will deliver a report of recommendations to the Commission that includes guidance on how to treat microgrids.

Microgrids are emblematic of the ever-changing electric power sector. They require innovation on the regulatory front as well as legislative flexibility. Broad stakeholder engagement is needed to provide the optimal regulatory framework. The diverse application of microgrids impacts their potential value to the end customer(s) as well as their regulatory treatment. In today’s changing energy landscape, jurisdictions that thoughtfully consider the regulatory treatment of microgrids, like D.C., will be best positioned to excel.

Jared Leader of the Smart Electric Power Alliance (SEPA) will be speaking at the HOMER International Microgrid Conference, October 7-9, in Cambridge, MA.

Improved Prospects for Grid-Connected Microgrids

Christopher Wiacek, Enel X, Enel X: Grid-Tied C&I DERs: A Global Market Perspective

Mike Murray, Ageto Energy, Microgrid Case Studies Utilizing Simplified Microgrid Controls

Gregg Morasca, Schneider Electric, A Model for Clean, Reliable Energy at the Nation’s Second-Busiest Port

Jared Leader, Smart Electric Power Alliance (SEPA), The Role of Microgrids in the 21st Century Grid

Join us at the Virtual 8th Annual HOMER International Microgrid Conference, October 12-16, 2020.