Like banks “too big to fail,” the grids in most developed nations are so fragile and interdependent that they are vulnerable to natural or human-made disasters that can cripple whole cities and regions. Microgrids, however, are like your local bank: independent from other local banks and thus much more resilient to unexpected future events. Resilience is an obvious benefit of breaking the grid system into smaller components independent of each others’ operation. But beyond resilience is an even greater force to consider in planning the future, and that force is antifragility.

The originator of this term is author and philosopher Nassim Nicholas Taleb, who devoted a 550-page book (titled Antifragile) to the topic. In the book, Taleb explores the need for thinking beyond resilience, because many models in business, science, and industry incorrectly predict the future through the past. The problem lies with unknown surprises (which Taleb calls “black swans”) causing major effects in world infrastructures, economies, and ecosystems. Taleb wrote about the possible collapse of the financial market in 2007. He was not making a prediction but an observation based on the market’s fragile nature.

Taleb expands on his theory in another book, The Black Swan. If we’ve never seen a black swan, we assume all swans are white–but the first time a black one appears, we find we were wrong. That black swan sighting instantly negates the logic of our previous system of thought.

An Australian black swan. Photo from: https://southperthlocalhistory.wordpress.com/2011/05/

“Black Swan effects are necessarily increasing,” Taleb writes, “as a result of complexity, interdependence between parts, globalization, and the beastly thing called ‘efficiency’ that makes people now sail too close to the wind.”

In a simple black swan example (helpful because the idea of antifragility is new to most of us), Taleb talks of a turkey. For his whole life, the turkey wakes up, goes outside, sees a human, and gets fed. This happens every single day. If you asked that turkey what humans are like, he would tell you, “They’re so sweet; they bring me food.” Then, right before Thanksgiving, the turkey sees a human, confidently goes to get food, and experiences a black swan event. We all know how the turkey’s unpreparedness for a black swan event works out.

Our current power systems and their failings are prime indicators of the sometimes devastating results of black swans on our fragile power grid. Some examples of fragility and its response to recent black swan events:

- When Superstorm Sandy flooded Manhattan with it 14-foot storm surge, a substation exploded and most of lower Manhattan lost power for several days. The power company lost a reported $500 million, and New York City businesses lost billions.

- Thailand’s 2011 floods knocked out auto parts supply chains, with auto production down, auto manufacturers suffered profit losses in the billions.

- Japan’s 2011 nuclear accident defied all plans and predictions by the Japanese government. Relying on faulty calculations of man-made systems, the country was not prepared for the loss of life, environmental issues, or financial disaster this fragile power system caused.

- In 2013, Super Typhoon Yolanda ravaged the Philippines, killed and injured tens of thousands of people, damaged power plants, and destroyed transmission lines. Severe power outages affected millions and full power in the country was not restored for months.

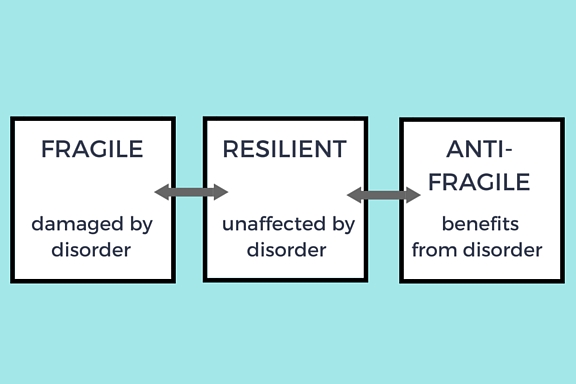

Microgrids and renewable energy create a much more resilient energy distribution system. However, like the turkey working only on known data, no one can project the effects of evolving issues, technologies, politics, global warming, war, drought–any of these events can and will change the game. This is where antifragility comes in. Taleb states that it’s an error to assume that the opposite of fragile is resilience. He argues that the true opposite of “gets weaker when stressed” isn’t “doesn’t get weaker” but is, instead, “gets stronger.” This distinction means that the microgrid world isn’t just resistant to major grid failures, but it can actually use black swan events as a means of improvement and growth.

Creating antifragile solutions will strengthen the economics of microgrids. Toward that end, microgrids and related systems can be built in a way that focuses on simplicity, creativity, adaptability, and the ability to evolve and improve with every black swan event and its lessons. The idea is not to predict the future better but rather be more prepared for whatever the future brings.

Regardless of field or industry, leaders can increase antifragility by challenging assumptions about traditional business models that stress short-term goals over the big picture. They can eschew systems that are overly complex and resource-intensive (thus decreasing physical footprint). Antifragility recommends creating teams with talented visionaries, building community support for our positive-impact projects (and focusing on those projects), incorporating environmental costs into business plans (as well as creating forward-thinking plans that incorporate innovation and redundancy), and partnering with others to create large-scale solutions unavailable to individual companies.

In addition to these principles, the microgrid/renewables field is particularly suited to antifragility. Here are just a few examples of black swan events that could occur:

- International environmental policies and regulations are happening quickly, and most of these changes are beneficial to microgrids. Likely or not, it’s possible the EPA or world leaders could soon set more stringent or very stringent emissions standards that propel the renewable energy market.

- Public perception and understanding of climate science will shift in the coming years. Public policy will be forced to shift along with it, whether slowly or almost instantly. Demand for renewable energy and microgrids is going to increase, we just don’t know how fast or how much. Cities (or even countries) may begin to promote resilient microgrids to guard against climate change.

- Extreme weather (or other) disasters may cause critical outages and grid-based issues that force a much faster switch to the microgrid model and renewables. It’s not inconceivable that these events could seriously cripple the very fragile financial system, affecting almost everything.

- Fracking may be banned because of environmental issues, leading to a faster timeline for energy alternatives.

- Gas prices may increase (and reserves of shale, oil, etc. decrease) faster than projected. Fossil fuel prices have proven to be volatile and may rise very quickly.

- Middle East instability may affect U.S. and world beliefs about relying on foreign oil, a concern that is already driving consumers toward renewables.

To avoid confusion, these are just examples; the idea of antifragility isn’t to make the best forecast but to examine the opportunities created by seemingly unlikely but high-impact events. Despite our projections, microgrids may do even better, even sooner, than we hope or can predict.

We can’t assume that any of these scenarios will play out, but microgrids will become increasingly successful in many future scenarios. Our technologies and manufacturing will continue to become cheaper, while extracting and delivering fossil fuels becomes more and more costly. Our products and services, often created for emerging markets, are designed to be simple and flexible. In the aftermath of black swan events, antifragility may exponentially increase our success.